The making of a 2D Software Blitter

Welcome to the second part of this… whatever. I won’t call it a tutorial. It’s essentially a presentation of the basic ideas behind #tofuengine software renderer. But you already know that.

In the previous part we’ve covered the basics on how to represent a 2D image in RAM, and how to perform the simplest blit (rectangular, opaque, with not clipping). Let’s continue from that and introduce…

Clipping

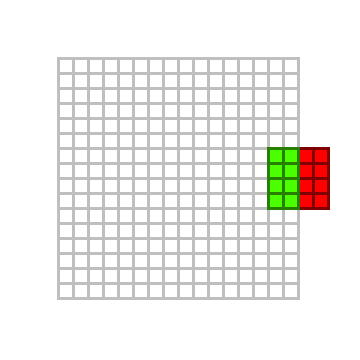

I’ve mentioned earlier that our gfx_surface_blit() function is going to have issues when drawing a sprite beyond the (rectangular) margins of the destination image. For example, if we were to try and blit a 4x4 sprite over a 16x16 image, starting at position <14, 6>…

… that would result in the two exceeding sprite’s columns of pixel appearing at the left-most margin of image, but with a 1-pixel vertical displacement. That should be obvious if we recall that we are representing our 2-dimensional image with a 1-dimensional array. The valid indexes for our array go from 0 to width * height - 1 = 16 * 16 - 1 = 31. As long as each <x, y> pixel we are drawing, once converted to an array index with the formula y * width * x = y * 16 + x, lies in this range we are safe from segfaults. However, if we don’t constrain x in the range [0, width - 1] = [0, 16 - 1] = [0, 15] (and similarly y in the range [0, height - 1] = [0, 16 - 1] = [0, 15], different <x, y> pairs could refer to the same array slot. For example, the third pixel (the red one) of the first row of our sprite lies at position <16, 6>, which is at the same index as <0, 7>.

This might seems just a courious glitch… but what happens if we increase x and y ending with one pixel at position <0, 16>. Yep… we get a segmentation fault, as index y * width * x = 16 * 16 + 0 = 32 lies beyond the array boundaries. The same happens when x and/or y are negative.

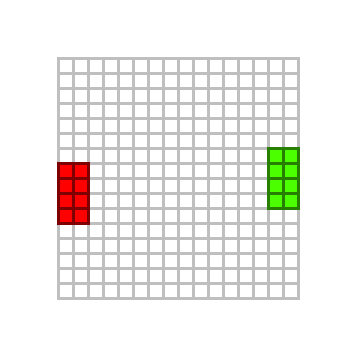

A downright naive solution to this issue is to limit x and y ensuring the sprite won’t overflow the destination image margins.

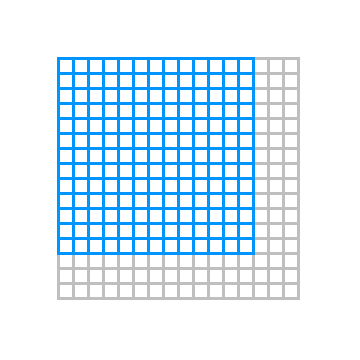

Using any of the blue pixels as top-left corner destination for our sprite will ensure no glitches at all. Perfect! Problem solved…

… as long as we are fine with our sprite being constrained inside the surface, like a ball on a billiard table.

But this also means we can’t partially draw our sprite across the destination image margins (like, for example, when a Pac-Man or a ghost enters one of the two warp tunnels at the sides of the maze to travel to the opposite side of the screen).

To accomplish that we need to perform an operation called clipping: when drawing the sprite, we need to compute the number of exceeding pixels (on the bottom-right) we aren’t going to draw, and the leftover pixels (on the top-left) we need to offset from the beginning of the data. An additional formal argument is required, i.e. the clipping region.

Rect holds four integer coordinates for a rectangle. The rectangle is represented by the coordinates of its 4 edges (left, top, right bottom). These fields can be accessed directly. Use width() and height() to retrieve the rectangle’s width and height. Note: most methods do not check to see that the coordinates are sorted correctly (i.e. left <= right and top <= bottom).

Note that the right and bottom coordinates are exclusive. This means a Rect being drawn untransformed onto a Canvas will draw into the column and row described by its left and top coordinates, but not those of its bottom and right.

// Similar to many other APIs (e.g. Windows' and Android's) the rectangle's the right and bottom

// coordinates are exclusive. This means that the last row and column of pixels are considered not

// part of the rectangle.

//

// The rationale is that this simplifies the rectangle width/height calculation, without adding

// complexity to the remaining part of the logic.

typedef struct gfx_rectangle_s {

int left, top;

int right, bottom;

} gfx_rectangle_t;

void gfx_surface_blit(gfx_surface_t *destination, int x, int y, const gfx_surface_t *source, gfx_rectangle_t clipping_region)

{

gfx_area_t drawing_region = (gfx_area_t){

.left = x,

.top = y,

.right = x + source->width, // Bottom-right row/column are excluded.

.bottom = y + source->height,

};

int offset_x = 0; // Offset in the source image, when moving top-left of the clipping-region.

int offset_y = 0;

if (drawing_region.left < clipping_region.left) {

drawing_region.left = clipping_region.left;

offset_x = clipping_region.left - drawing_region.left;

}

if (drawing_region.top < clipping_region.top) {

drawing_region.top = clipping_region.top;

offset_y = clipping_region.top - drawing_region.top;

}

if (drawing_region.right > clipping_region.right) {

drawing_region.right = clipping_region.right;

}

if (drawing_region.bottom > clipping_region.bottom) {

drawing_region.bottom = clipping_region.bottom;

}

const int width = drawing_region.right - drawing_region.left;

const int height = drawing_region.bottom - drawing_region.top;

if (width <= 0 || height <= 0) {

// No pixels to be drawn! We use signed integers as `width` and/or `height` could be negative due to

// the independent corner-bounding.

return;

}

gfx_pixel_t *dptr = destination->pixels + drawing_region.top * destination->width + drawing_region.left;

const gfx_pixel_t *sptr = source->pixels + offset_y * source->width + offset_x;

const int dskip = destination->width - width;

const int sskip = source->width - width; // Also the source surface is potentially to be skipped.

for (int i = height; i; --i) {

for (int j = width; j; --j) {

*(dptr++) = *(sptr)++;

}

dptr += dskip;

sptr += sskip;

}

}

Sprite-sheets

Now we finally can draw sprites everywhere around another surface. How cool is that!

So we can proceed and draw distinct images, each for one of our sprites (and for each frame of each sprite). Load them into an array of images, and draw when by indexing the required one with an index. Something like this

// We assume this function has been implemented somewhere else...

extern gfx_surface_t *gfx_surface_load(const char *pathfile);

// ... and also this, returning a randomized integer.

extern int random_int(int min, int max);

#define SPRITES_COUNT 8

static const char *_sprite_pathfiles[SPRITES_COUNT] = {

"assets/images/ship-up.png",

"assets/images/ship-left.png",

"assets/images/ship-down.png",

"assets/images/ship-right.png",

"assets/images/bullet.png",

"assets/images/enemy-star.png",

"assets/images/enemy-ball.png",

"assets/images/enemy-spikes.png"

};

int main()

{

gfx_surface_t *background = gfx_surface_create(320, 240);

gfx_surface_t *sprites[SPRITES_COUNT] = { 0 };

for (size_t i = 0; i < SPRITES_COUNT; ++i) {

sprites[i] = gfx_surface_load(_sprite_pathfiles[i]);

// We should check for errors, of course...

}

for (size_t i = 0; i < 128; ++i) { // Draw a bunch of random-positioned sprites.

int x = random_int(-400, 400);

int y = random_int(-400, 400);

int id = random_int(0, SPRITES_COUNT - 1);

gfx_surface_blit(background, x, y, sprite[id]);

}

for (size_t i = 0; i < SPRITES_COUNT; ++i) {

gfx_surface_destroy(sprites[i]);

}

gfx_surface_destroy(background);

return 0;

}

This will surely work… but with some issues/annoyances. First of all, the extensive and boring boilerplate code required to handle an array of surfaces (in our example we used an automatically stack-allocated array, which is straightforward, but in a real-world example the array would have been dynamically allocated which is even more annoying). Secondary, for every sprite a specific surface is allocated, which causes memory additional memory usage and fragmentation. But most importantly, for each sprite draw operation, we are dereferencing a distinct heap memory chunk this continous switching is almost certainly going to cause cache misses due to bad/absent exploit of the principle of locality (we would say that the code is not cache-friendly).

The solution to all this has a name: sprite-sheets1. The idea is elementary: organize and pack the whole bunch of sprites into a single surface. Now, all the sprites can be read with a single call into a surface.

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

gfx_surface_t *background = gfx_surface_create(320, 240);

gfx_surface_t *atlas = gfx_surface_load("assets/images/atlas.png");

// How we are going to draw them?

gfx_surface_destroy(atlas);

gfx_surface_destroy(background);

return 0;

}

However, we cannot use the gfx_surface_blit() function we already wrote. If nothing at least for it copies the whole sprite onto the destination surface. We need to rework it a little and enable copying of only a part of the original surface (i.e. the sprite-sheet). For that reason, we define a new type (gfx_cell_t) used to hold the position and size of the portion of sprite-sheet we want to draw.

typedef struct gfx_cell_s {

int x, y;

int width, height;

} gfx_cell_t;

void gfx_sheet_blit(gfx_surface_t *destination, int x, int y,

const gfx_surface_t *atlas, gfx_cell_t cell,

gfx_rectangle_t clipping_region)

{

gfx_area_t drawing_region = (gfx_area_t){

.left = x,

.top = y,

.right = x + cell.width, // Bottom-right row/column are excluded.

.bottom = y + cell.height,

};

int offset_x = cell.x; // Initially we offset to the origin of the sprite, we'll update if required.

int offset_y = cell.y;

if (drawing_region.left < clipping_region.left) {

drawing_region.left = clipping_region.left;

offset_x += clipping_region.left - drawing_region.left;

}

if (drawing_region.top < clipping_region.top) {

drawing_region.top = clipping_region.top;

offset_y += clipping_region.top - drawing_region.top;

}

if (drawing_region.right > clipping_region.right) {

drawing_region.right = clipping_region.right;

}

if (drawing_region.bottom > clipping_region.bottom) {

drawing_region.bottom = clipping_region.bottom;

}

const int width = drawing_region.right - drawing_region.left;

const int height = drawing_region.bottom - drawing_region.top;

if (width <= 0 || height <= 0) {

// No pixels to be drawn! We use signed integers as `width` and/or `height` could be negative due to

// the independent corner-bounding.

return;

}

gfx_pixel_t *dptr = destination->pixels + drawing_region.top * destination->width + drawing_region.left;

const gfx_pixel_t *sptr = atlas->pixels + offset_y * atlas->width + offset_x;

const int dskip = destination->width - width;

const int sskip = atlas->width - width;

for (int i = height; i; --i) {

for (int j = width; j; --j) {

*(dptr++) = *(sptr)++;

}

dptr += dskip;

sptr += sskip;

}

}

As you might have noticed, we changed only a few lines of code. We just need to initialize a different (initial) drawing region and take into account the cell position when offsetting into the source surface (the atlas).

As a result the previous function behaviour, that is copying the whole source surface, is just a special case when

cellpoints to<0, 0>and matches in width and height the source surface.

We can new complete the drawing code like this

static inline gfx_cell_t _id_to_cell(const gfx_surface_t *atlas, size_t cell_width, size_t cell_height, size_t cell_id)

{

const size_t columns = (size_t)atlas->width / cell_width;

int x = (cell_id % columns) * cell_width;

int y = (cell_id / columns) * cell_height;

return (gfx_cell_t){ .x = x, .y = y, .width = cell_width, .height = cell_height };

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

gfx_surface_t *background = gfx_surface_create(320, 240);

gfx_surface_t *atlas = gfx_surface_load("assets/images/atlas.png");

// How we are going to draw them?

for (size_t i = 0; i < 128; ++i) {

int x = random_int(-400, 400);

int y = random_int(-400, 400);

int id = random_int(0, SPRITES_COUNT - 1);

gfx_cell_t cell = _id_to_cell(atlas, 16, 16, id); // Convert cell id to area.

gfx_sheet_blit(background, x, y, atlas, cell);

}

gfx_surface_destroy(atlas);

gfx_surface_destroy(background);

return 0;

}

In a real world scenario, we would create a new user-data-type like this

typedef struct gfx_sheet_s {

gfx_surface_t *atlas;

gfx_cell_t *cells;

} gfx_sheet_t;

with all the required functions to allocate/initialize/load/deallocate the UDT. During the sprite-sheet initialization the cells array would be allocated and initialized with either equal-sized cells (this can be easily computed in a similar way as displayed in the _id_to_cell function), or with independently sized cells loaded from a description file (e.g. created with a [suitable tools(http://free-tex-packer.com/)). Then, sprites can be identified and referenced with an array index (i.e. the cell identifier).

Next to come

We have finally completed the basics. In the next installement, we’ll extend our blitting code by adding transparency and colour shifting.

-

Also known as sprite banks or sprite atlases. ↩